Thanator survived the Cataclysm only by becoming a theater for savagery, its glory permanently broken; Vandyrus, by contrast, was battered, fractured, and forced to heal wrong.

Its bones are hollowed by disaster, its civilizations lashed into dust and mud, every new era merely a repetition of the last—a cycle of rise, collapse, and forgetting. Nothing built here ever stands straight. The past is not inspiration, but a constant ache: every living culture senses the shape of what was lost, and cannot escape the knowledge that nothing here was ever whole.

For Vandyrus, the Cataclysm is not an event but an unending chain—a succession of blows, each one proof that the cosmos is indifferent to suffering or survival. The history known today is a patchwork of rumor, scavenged myth, and the dying embers of dead cities. The only records that persist are the desperate scratchings of survivors who watched the sky turn to fire, the land itself become hostile, the world shift beneath their feet. Vandyrus never built the crystal towers or star-thrones of Thanator. Its height was measured in ziggurats and stone halls, monuments to vanished gods, quickly reclaimed by salt, mud, and time.

The Cataclysm has no true name. Sages call it: Doom.

Vandyrus was struck by three great impacts—each powerful enough to shatter continents, poison seas, tilt the very axis of the world. But these were only preludes. Behind them came the Cataclysmic Object, a thing of monstrous gravity, dragging a cloak of ruin and fire, cursing the land and sea for generations.

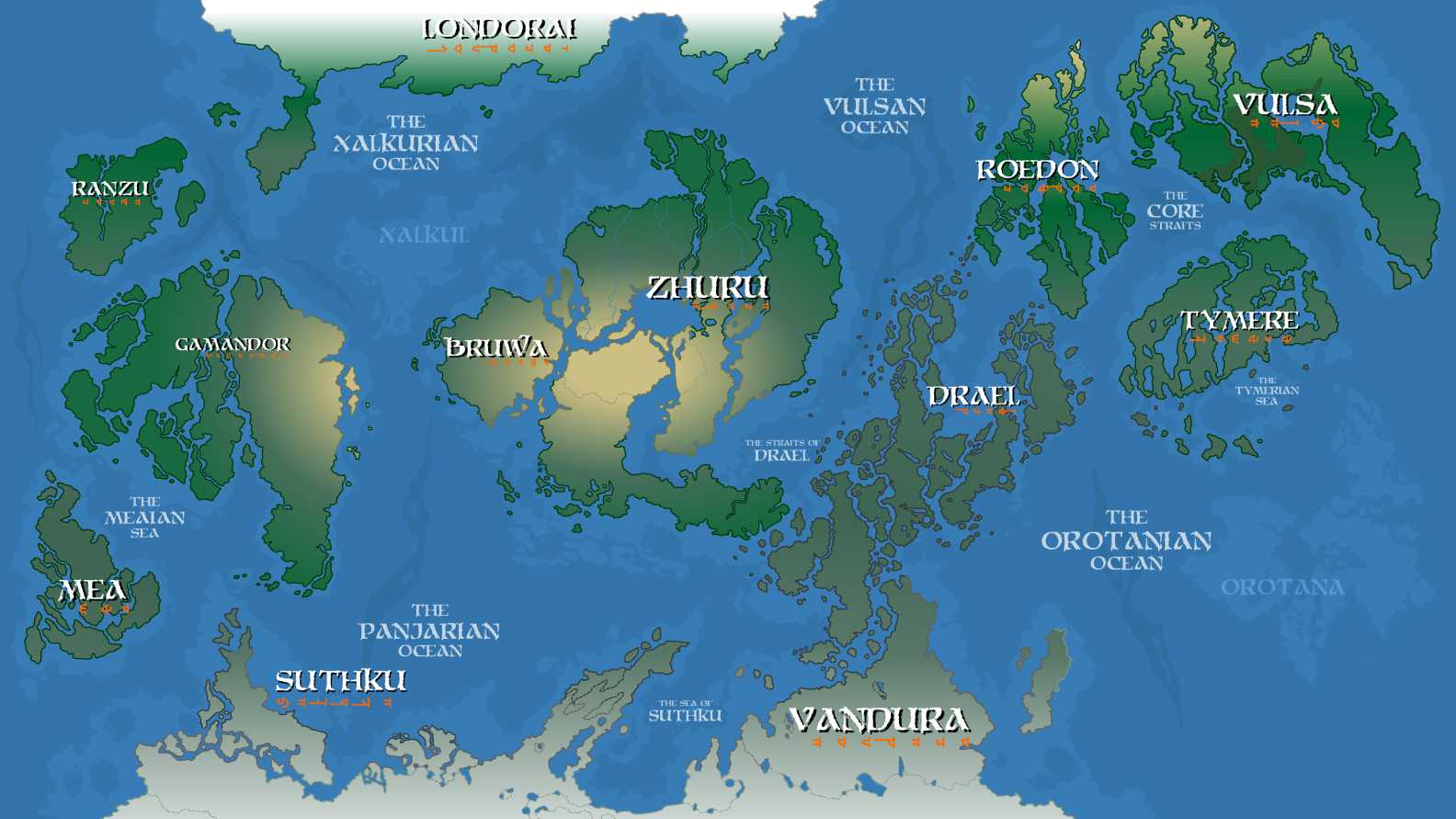

Zhuru might have been a heartland, but the Cataclysm left it buckled and stripped bare, its grasslands now haunted and rivers sterile, its cultures surviving only as scattered, mistrustful bands.

Drael took the brunt: its spine broken, its surface split into peninsulas and chasms. Life on the surface was erased; what survived fled below.

Yet long before the cataclysm, the serpent folk built thrones in the deeps, while the surface became hunting ground for raptor and dragon—scavengers circling a world never theirs. Gamandor was gutted by aftershock and rot. Xalkul’s towers sank beneath the sea, Orotana’s memory is now only a curse. Vandura and Panjar bear wounds older than language, their dynasties just arrangements of scar tissue.

Suthku and Londorai, on the system’s edges, were not spared. Suthku broke, drifting south into a wasteland of half-empty cities. Londorai’s ancient realms fused beneath the ice, its folk surviving not by hope but by stubbornness, bitterness, and spite.

When the Cataclysm ended, history itself ended with it. What is remembered now is handed down as rumor, as warning, as bitter song. The common tongue of Vandyrus is a corruption of Thanator’s colonist speech, warped by abandonment and the need to rebuild from the bones of the lost. Even in language, survival takes the shape of failure.

But Vandyrus did not die. It refused to yield.

The Vandyrian Atlas

Now In Production

Book II: The Ancient Histories