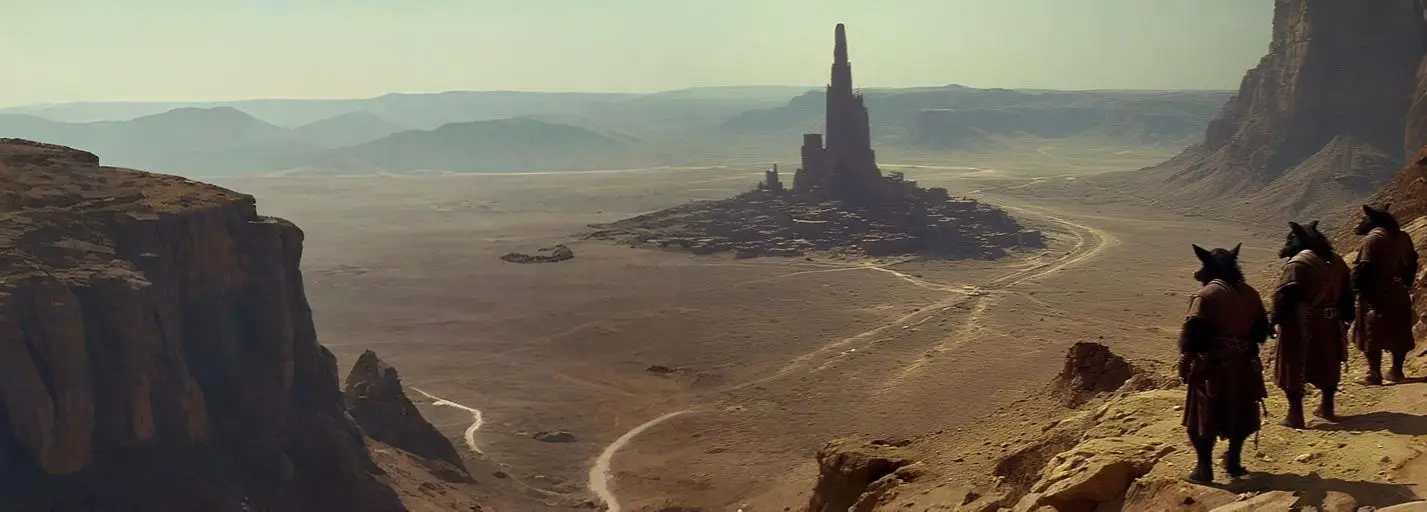

“Tentus is the open mouth of Drael, a city squatting in the bowl of an ancient impact scar where stone was once turned to vapor and sky burned white. It is not among the four great thrones of the north, nor does it pretend to rival the hidden citadels beneath ash and serpent-ruin, yet it endures because it performs a function none of the greater powers care to soil themselves with: exchange. Trade, vice, spectacle, execution. If Drael is a wound, Tentus is the clot that never quite seals, thick with caravans and carrion both. Drael itself is described in the old tablets as inverted—surface ruin masking subterranean dominion.

Tentus is surface made permanent. The crater’s rim forms a natural amphitheater, jagged stone rising in broken arcs like teeth around a tongue of dust. At its center yawns the Pit, a vast arena carved deeper into the impact basin, ringed by terraces of basalt and bleached bone. From above, the city appears circular and organic, streets spiraling down toward the Pit in widening coils, each ring a district of trade, degradation, and ambition. The Deinonychus lords claim Tentus as neutral ground. Whether they truly rule it is debatable. The scaled barbarian tribes of Drael’s surface—raptor packs, Spinosaur flotillas from the marshes, feather-crested velocian assassins—send emissaries and enforcers, but none sit a permanent throne there. That absence is deliberate.Tentus thrives because no single warlord dares claim it entirely. To do so would disrupt the delicate machinery of vice and barter that feeds all sides.”

I

Dust came first—the long brown veil that rose from the ash flats and stuck to her tongue, that scoured her cheeks when the wind came hard across the old bones of the land. She felt it against her horns like grit against stone, a rasping kiss that told her the road to Tentus was near. The mature styracosaur shaman took the rise slow, spear butt clicking on fractured slate, axe slung at the hip for anyone foolish enough to think a hungry tribe meant a helpless envoy.

Her bosom lay heavy beneath her harness, wrapped in worn blue cloth that smelled of sage and smoke; her blue cheeks had the habit of flushing when the sun broke free of cloud, and it did so now, throwing a hot stripe across her face that made her blink and squint.

The heat kept the scent of her sweat close. The heat made the flies bold. The heat made everyone on this broken road irritable and dangerous, and she counted on that because danger kept true, while promises were a softer breed of lie.

They noticed her as they always did. A pair of lizard porters with scarred tails, bellies gaunt beneath their belts; a crocodilian pilgrim draped in river beads and old reeds; three hyena sellblades who were laughing at nothing and everything. Males let their eyes fall to her cleavage and then bounce up when they remembered the horns. She did not mind the appetite—appetite made the world move—and she did not slow.

She had been told the brown allosaur in Tentus sometimes traded favors for favors —She had been told he bartered in flesh and spectacle as much as in coin. She had been told many things by storytellers who had never rutted with hunger or looked down the long throat of a dying season. The steppe behind her had gone to rust and thorn. The last calves had fallen. What she carried now — a few trinkets, a bundle of salt-cakes, and a prayer — was not a bargain. It was an excuse to be seen.

The grass had grown tall and then fallen in the wrong storms, mold taking it in a soft black creep that killed what cattle they dared keep near the marsh. The hyenas who crossed the sea had burned what they could not carry—this was their humor—and the tribe’s store-caves now breathed like hollow mouths.

She’d taken the last of the good salt cakes, the rolled canvas of medicinal moss, the small jar of sun-thick honey beads, token gifts to grease tongues. It would not be enough. It had never been enough with Tentus; that city ate in the rhythm of drums and spent in the rhythm of hips, and called it order.

On the high road into the basin she paused to piss, turned away from traffic toward the split slate and the sparse weeds. Relief warmed her thighs, then cooled in the breeze. When she straightened, adjusting the wrap at her chest, a young iguanodon with a rusty mask of paint stood ten paces off.

His eyes had the skittish shine of those who ran messages; his tail twitched a pattern that meant fear trying to dress up as bravado. He kept his head low but his stare low too, fixed where the blue cloth crossed and pressed her bosom together.

“You’ll get yourself hurt looking like that,” she told him without heat. “I’m only looking at what’s there,” he said, a little too quick, and stepped back when she shifted the axe on her belt. “You go to Tentus?”

“I go to whoever will sell me a season.” She picked up her spear and shouldered past. His scent was salt and young rut and the dust of the road, and it faded behind her soon enough because the city smell took over—blood smoke, meat char, latrine stink, perfume of cut sap from the arena stakes, and the hot iron breath of the forges where bone and bronze met and disagreed.

Tentus crouched in the basin like a jackal that had eaten too much and still wanted more. Its stone teeth rose in jagged palisades patched with old idols, shellacked with the fat of festivals and the filth of losing nights.

She had come as a girl once, more horn than sense, with her mother’s voice still in her ear; she had come again as a healer walking the plague lines when the flies overtook the river rats and a fever cut through the ribbed poor like a bright knife. Now she came as something else, something like a merchant but with nothing to sell but her dignity and what flesh the gods had given her.

She spat to throw the thought out like a bad seed. It clung anyway. At the gate the guards played their usual game—ask a little too much, hope for a bribe, stare a little too long at the curve of her chest to see if blushing might open her purse. She let the blush come; she could not help it in this heat. But when the shorter of the two, a skink with a gold ring between his nostrils, drifted from stare to step, she tapped the haft of her spear once on the stone.

The sound was not loud. The sound said: consider the points at the end and the weight of the axe and the weight of my patience. They stepped aside. Her sandals took city stone. Inside the wall, Tentus moved like meat on a spit. Hammocks swayed with dripping females, bosoms pierced, coins dancing between thighs; dust devils collected cheers in the arenas and flung them down again; a butcher’s boy wrestled a slab of purple meat while a crowd bet whether it came from something with feathers or scales;

Somewhere a priest hissed funeral words over a bloated corpse, a pale snake coiled in his hands, its tongue flicking the dead man’s lips as if to taste the soul and pass arcane judgements.

She angled past a canvas where females oil-slicked and laughing wrestled on their knees while some born-to-crown fool sprayed a rain of coins to watch them slap. The coins fell too fast and rolled in dust; fate had that habit

Vendors shouted inventories that sounded like poems. Needles for stitching hides. Needles for stitching holes in the meat. Needles for stitching holes in pride. Clay balls filled with musk for males who needed to smell stronger than they felt. Glass beads that turned sunlight into knives to scare carrion birds.

She tasted iron on the air and thought of her tribe’s huts and how the wind went through them too easily now that the hyenas had given the rafters to fire. She did not pray. She had already prayed on the ridge when she saw the road. The gods had given their answer in the shape of this city and its appetites.

A gambler’s drum took up a steady beat as she wound toward the war-quarter, a simple three-note call that meant numbers were going to be found out one way or another. The brown allosaur kept a hall near the bone-yard where the old champions’ skulls were stacked and stacked until the smell of lacquer and pride hung thick. His name did not matter; names changed with throats. What mattered was that his appetite was the sort that made caravans move and starving villages bend, and that he had sent word through salt lines that he would make trades if the trade amused him.

She could smell the pipe resin they said he liked from halfway down the narrow. She stopped at the hall mouth to straighten her wrap. She tightened the blue cloth over her bosom, a gesture of modesty that was really just armor. She rolled her shoulders once, pulling aches into the sockets where they belonged, and felt the old strength cinch around bone and sinew like a belt. Males would watch her walk in; they always watched.

They would measure her hips and her chest and the length of her horns and pretend that was the same as measuring her will. She let them think it. Then she stepped into the shade, spear at her back, axe at her hip, hunger at her heels, and the smell of resin and smoke unrolling ahead like a promise that tasted exactly like a price

II

The Allosaur Warlord did not greet her at once. He never did with petitioners. He sat sprawled at a bone-table slick with meat and fruit, the smoke of his resin pipe curling from his nostrils as though to draw a boundary around her in the air. He chewed and spat, tore cartilage with teeth made for rending, not savoring, and let her stand in the shadow while the minutes dragged.

When she shifted her weight, the crack of a spear-butt on stone snapped through the hall. His servant hadn’t been told; the gesture was instinct. The message clear. Patience was his, not hers.

She endured. She had endured the screams of fever victims as their tongues blackened. She had endured the smell of her tribe’s huts when the hyenas lit them. She would endure this too. But every crunch of bone between his jaws was meant for her, each wet suck of marrow another reminder that she was prey standing before a predator’s table.

At last he wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and leaned back. His eyes found her bosom first, not her horns, not her arms. He stared with the lazy hunger of a drunk too full to bother pretending. The grin came slow, curling his lip until the smoke bled between his teeth like steam escaping rock. His tail flicked once, twice. The guard’s spear dipped half a handspan. That was all it took for her to know the balance had shifted.

“Food. Resources. Materials,” she began, forcing steadiness she did not feel. “The hyenas leave us nothing but ash. My people starve. You know this.”

“I know what I hear,” he said, voice thick with grease and smoke. “I hear weakness. Matriarchs who cannot defend their nests. Horns like banners, tits like milk-jars, and still you come here begging.”

He sucked the last shred of marrow from a bone and tossed it aside, where it landed near her foot like a warning. “Why should I not feed you to the pit and let the crowd laugh at your squeals?!”

Her grip on the axe tightened, though she kept it low. “Trade profits both,” she said. “You have stores. We have—”

He barked a laugh, low and scornful. “You have nothing. Nothing but that.” His chin dipped toward her chest. The twitch in his jaw told her exactly what he imagined. “And that, shaman, is worth more to me than all your starving tribes.”

Her stomach burned, but she stood her ground. This was Tentus. To flare, to draw blood, was to lose everything.

He rose, slow and deliberate, his scars catching the firelight. The pipe swung from his lip as he circled her, tail scraping the flagstones. His musk thickened the air. Servants withdrew without a word. The hall fell silent but for his steps and her breath.

“You came to beg,” he said at her ear. “Now you will beg properly.”

He did not touch her then. He only returned to his furs, took up another rib, and began to eat again as if she had already ceased to exist.

Hours passed. He heard messengers. He counted coin. She waited, motionless, the ache in her thighs spreading into her back. The smell of grease and fruit thickened the air until it felt like another punishment.

When he finally flicked a claw in her direction, it was without looking up. “Come.”

And she knew that whatever bargain would be struck, it would not be struck in words.

III

He lounged like a prince of bones, thick tail stretched across the furs, cock buried deep inside of her warmth already, a spear that had claimed far too many victories in the past.The styracosaur shaman straddled him, blue hips rolling, flushed bosom swaying, sweat dripping from her horned brow. Her thighs trembled from labor; the ache in her back had grown into a constant burn.

Yet he did nothing but recline, wine cup balanced in one claw, smoldering rib-meat dripping fat down the other, yellow eyes half-lidded with pleasure.

His shaft stayed stone-hard, but not through any effort of his own—she was the one doing all the work, grinding, bouncing, moaning, trying to coax his release again and again.

“Pathetic,” he said around a mouthful of charred flesh, voice rumbling like an insult carved into her marrow. “You sweat and squeal like a sow, and still your tribe starves. What good is a matriarch who cannot even rut properly?” Her blue cheeks burned darker, shading toward purple.

Rage, shame, arousal—all knotted so tightly she could not untangle them. She tried to form words, to explain, to deny, but his claw came down on her bosom with a stinging slap that made her squeal like a calf.

“Then go back,” he sneered, pinching her nipple until her vision blurred. “Go rut with your own weak males. Let them pant and dribble seed into you while your children chew bark.”.

His laughter was cruel as she worked her naked blue flesh above him. Her protest caught in her throat. Every time she had spoken, he had silenced her with laughter, with pain, with command. So now she moaned instead, high and desperate, hips working faster in spite of herself. Her cunt clutched him, slick and clenching, betraying her station and her disgust alike.

He drained his wine and held the empty cup aloft. A slave hurried to refill it, eyes flicking to the shaman’s bouncing bosom, lips twisted in a smirk of mockery. Others brought trays of meat, the scent of charred beast heavy in her nostrils. She recoiled, stomach tightening at the sight of him tearing sinew from bone even as his cock throbbed inside her. He relished her disgust, chuckled when she flinched.

“You hate it,” he said, snapping bone with his teeth. “You hate that I eat while you serve. But your tight fat cunt… ah, it relaxes me. A good suckling cunt, full of heat. You might even be worthy of it, if you learn.” Her teeth ground together. She hated him. Hated the way her body betrayed her, hated the way her nipples stiffened under his claws, hated the way the flush of her cheeks slid purple with need.

She whined, high and trembling. “I have been at this for hours…”

“Hours?” He laughed, deep and cruel. “Hours are nothing. A true vessel milks her master until his hunger is drowned. Watch.”

He seized her tit, yanked until she shrieked. She had learned: arms behind her head. Her bosom thrust forward, vulnerable, obedient.

He nodded, satisfied. Slaves lingered, watching her rut while handing him another rib, another jug of wine. She squealed with each thrust, not daring to stop, not daring to falter. The shaman loathed every gaze upon her, loathed the way they whispered and smirked. Her tribe’s enemies would starve her kin, and here she was, sweating, bouncing, riding the warlord’s cock while he feasted.

“Perfect,” he said, chewing loud. “Seed and meat together—what more could a male want?”

She saw the moment come: his jaw snapped bone, fat running down his chin, and at the same time he groaned and spilled inside her. She recoiled, horror surging like bile—yet she forced herself to stay, forced herself to present, cunt swallowing his spurts, bosom bouncing in rhythm to his release.

She nearly slapped him, nearly broke the spell with fury—but he saw it in her eye, grinned, and dragged her down hard, burying her to the root. Her head snapped back, scream tearing the air like a prayer that would never be answered.

Her hips ached, bosom slapped against his chest, sweat rolled down the blue of her cheeks until the flush had turned purple. “Too stiff,” he sneered, giving her breast a sharp slap. “Roll your hips, cow. Spiral it. You’ve got potential.” She gritted her teeth, hating that his words cut both ways—mockery, and yet a kind of instruction.

This was not how things were done in her tribe; rutting was quick, fierce, equal. Here she was reduced to squealing and whining, her arms behind her head on his command while his slaves looked on and laughed. “You’ll learn,” he drawled, tearing a rib in half with his teeth. “A good suckling cunt deserves training.”

Her thighs trembled, but the allosaur only leaned deeper into his furs, belly streaked with grease, cock jutting skyward like the mast of a war-raft. Still, She rolled her hips, forcing the spiral he demanded, bouncing hard and fast, breath breaking in sharp whines. Every movement sickened her—this was not rutting, not the way her people knew it—but her cunt betrayed her, clutching his shaft, sucking him deep. His eyes burned yellow-gold as he sipped his wine and let her do the work. Her loathing was a hot coal inside her, yet her body betrayed her—cunt clenching, hips rolling in figure-eights just as he’d shown.

He drank deep, swallowed meat, and when the second orgasm ripped through him, he timed it with a swallow, moaning as if her tightness and the taste of charred flesh were the same pleasure. He pulled her down hard, burying himself, and she screamed, not in triumph but in horror that her body had obeyed so perfectly.

When she licked her lips, desperate for water, he barked a laugh. “Thirsty? Here, cow. Drink.” He caught her by the horns and poured the wine down her throat, red and sharp, burning her tongue, filling her belly with fire. She coughed, sputtered, swallowed, and the world lurched sideways—the walls bent, the smoke curled into shapes, the slaves’ faces swam. The wine was too strong, drugged or simply bred for a stomach thicker than hers. He roared with laughter as she swayed atop him, grinding harder, looser, her cunt slicker for the heat in her veins.

“Good! I feel it. Loosened up, little cow. You ride better drunk.” His claws dug into her ass, spreading grease across her hide, smearing rib fat onto her flanks until her rump gleamed with it.

Her backside slid against his scaled thighs, oiled not with perfume but with the juices of his feast. She gagged on the stench—meat, smoke, resin, sex—all tangled together. Each slap of her hips smeared more grease over her haunches, down between her thighs, until she was painted in his appetite. The slaves smirked as they brought another tray, staring openly at her bosom as it slapped against his chest. She wanted to cry out, to curse, but the wine made her moan instead, a low animal sound that sent him over the edge.

He bit down on a rib, swallowed a hunk of meat, and groaned as he spilled into her, spurting seed while grease ran from his claws onto her ass. He timed it perfectly, chewing, swallowing, and ejaculating in one lazy rhythm, as though she were just another dish in his banquet. She screamed—whether from orgasm, horror, or both she no longer knew—and collapsed forward, her bosom crushed to his chest, her cunt clenching on his shaft even as she hated every second. He laughed, belly shaking, and licked wine from his teeth. “Perfect. Meat and cunt, the two true gifts. And I get both at once.”

She sagged against his chest, bosom pressed flat and glistening with sweat, cunt still fluttering around his cock though he had emptied into her many times already.

Her breath came in sharp squeals. He only leaned back further, smearing grease into her hide with the casual stroke of a claw, laughing deep in his throat. “Look at you,” he said, tilting her head back by her horns so he could see her cheeks. “Not blue anymore. Purple. That’s what a real male’s seed does. Paints your face with heat. Shows the truth of you.” She snarled, low and desperate, but the wine made it break into a moan. The floor swam beneath her hooves, the walls twisted into coils of smoke, and still his cock stood iron-hard inside her. She tried to slow her hips, to catch her breath, but his claw slapped her bosom again, the sting making her squeal high and pitiful. “Not enough,” he mocked. “Not nearly enough. Roll them wider. Spiral your hips, cow. Yes. That’s how you milk me. Don’t stop. Don’t you dare stop.”

She obeyed. Not because she wished it, but because every time she resisted, his claw pinched her nipple until her eyes watered and the slaves laughed. She hated their stares, hated the smirks curling their muzzles as they filled his cup, as they dabbed grease from his scales only to smear it across her rump. Her backside was slick now, shiny with meat-fat, each bounce making a wet slap against his thighs. “A thick matriarch begging with her cunt.” he said, chewing loud, flecks of flesh falling into the fur beneath them. “A Grass eater. A vessel of weakness. Do your horns tremble knowing you were bred for this?” Her cunt betrayed her again, clenching hard around him. She threw her head back and moaned, ashamed at how deep it struck her.

Loathing gnawed her, not only for him but for herself. She had never been skilled in the ways of sex; her station had allowed few chances. Now she found herself guided like a calf in the pen, taught how to grind, how to squeal, how to please a carnivore who tore meat with his teeth even as he spilled into her womb. He poured more wine down her throat, and she swallowed in desperation, tongue thick, belly burning.

The hallucinations deepened—his teeth gleamed like moons, his tail like a serpent winding the hall. Her body moved easier, looser, driven by drug and humiliation both. “Good,” he chuckled, tugging her arms back behind her head again. “fat tits high. Cunt tight. This is how you’ll beg for me.” She squealed, purple blush staining her cheeks, and rolled her hips in violent figure-eights. Her breasts bounced with each thrust, fat and heavy, slapping against her chest while his claws tugged and twisted. She hated him. Hated herself more. But her body reached anyway, her cunt rippling, pulling, dragging his seed from him until he groaned and thrust once—just once—and spilled into her, yet again.

He swallowed meat as he came, grease dribbling onto her ass, his laugh shaking his belly. Pressing down onto her thick trembling rump as he ejaculated long and deep into her. “There,” he said, patting her tit as though marking a tally. “and Just three more before the sun sets.” She whined, high and broken, but kept grinding because protest had earned her nothing but pain, and obedience at least gave her the rhythm of his release. Her eyes rolled back as the searing heat of his load washed over deep inside of her.

Epilogue

The door flap had barely fallen shut behind the styracosaur when he barked a laugh, slapped his thigh, and raised his cup. Resin smoke and meat fat hung heavy in the hall. Her axe and spear leaned against the bone-table, gleaming with fresh grease where he had touched them, already claimed as trophies. “Look at that,” he said, stretching out long in his furs, cock still streaked, belly full. “Big horns, heavy tits, a matriarch of grass-eaters — and I sent her out of here bow-legged, leaking, and unarmed. I let her keep her rags. Jewelry alone would’ve been prettier, but…” He blew smoke toward the rafters.

“Better to let her keep a scrap of dignity. That way when she comes crawling back, I can strip it from her slow.” The slaves chuckled, sharp teeth flashing. One poured wine; another laid a new tray of ribs. He ignored them as he always did. He wasn’t talking to them. He wasn’t even talking to anyone in particular. He was talking to the hall, to the rafters, to the bones, to himself — because he knew every claw and fang in his war-band could hear him, and they were grinning in their guts. “They call me a pain in the eye of civilization,” he said, chewing slow. “Good. To horn-cows and grass-eaters, I am pain. To hyenas across the sea, I am nightmare. But to my raptors? To my pack?” He raised the rib in salute, grease running down his arm. “I am king.” He leaned back, sighing through smoke.

His grin widened as he saw her spear glint in the firelight, his trophy now, proof of her humiliation. “Six times I spilled, and she rode every drop. Didn’t matter if she blushed, didn’t matter if she cried, didn’t matter if she hated it. She worked for me. She bled sweat for me. She learned my rhythm.” He licked the last of the grease from his claw. “That’s civilization. That’s Tentus.” The hall laughed with him, a chorus of snorts and tail-slaps. He drank deep, wine staining his jaw, and thought of her purple cheeks, her squeals, the way she staggered out with her head down. He had given her nothing but “consideration,” and still she would come back. They always did.

The laughter of the hall faded behind her, swallowed by the dust and the wind. She staggered up the embankment barefoot, the blue cloth clinging damp to her bosom, every step a throb between her thighs. Her axe and her spear were gone—his trophies now, shining in the firelight of Tentus. She cursed him under her breath, cursed the city, cursed the hyenas across the sea. Each oath felt thin, rattling out of her beak like brittle shells. The road stretched long and gray ahead, the grass withered to stubble. Her horns ached, her bosom burned from his claws, her cunt still leaked in thick pulses.

She tried to spit, to clear the taste of his wine from her tongue, but the fire lingered in her belly, the heat it had kindled refusing to leave. And in the hollow of her mind, in the place she would never speak aloud, she knew the truth: it was when he had been most despicable that her body had betrayed her most. When he had eaten meat and laughed, grease dripping on her ass, when he had called her a cow and slapped her tit raw, when he had spilled into her with his mouth still chewing—that was when she had felt her flush deepen, her hips loosen, her heat rising.

She hated him for it. Hated herself more. The shame scalded worse than the bruises. She pressed her thighs together as she walked, but the ache only grew, a cruel rhythm that matched the memory of his belly shaking with laughter. Behind her, the smoke of Tentus climbed the sky.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon