No single world in Ran was ever conceived as a sovereign anomaly. Each was raised, shaped, corrected, or broken according to something immeasurably older and vastly more complete than any local empire, dynasty, or planetary myth. These worlds were components, not centers—expressions of a greater civilizational architecture whose logic predates any one star, system, or epoch.

The empires that arose within Ran did not emerge spontaneously, nor were they the product of linear cultural ascent. They were instantiations of a template: a repeatable, adaptable system of conquest, administration, extraction, and meaning-making that has been deployed across uncountable theaters of existence. This template is what later scholars would name the Vandyrian Systema—not a single empire, but an imperial grammar. Worlds differ in surface culture, biology, technology, and belief, yet beneath these variations the same structural bones recur with unsettling precision.

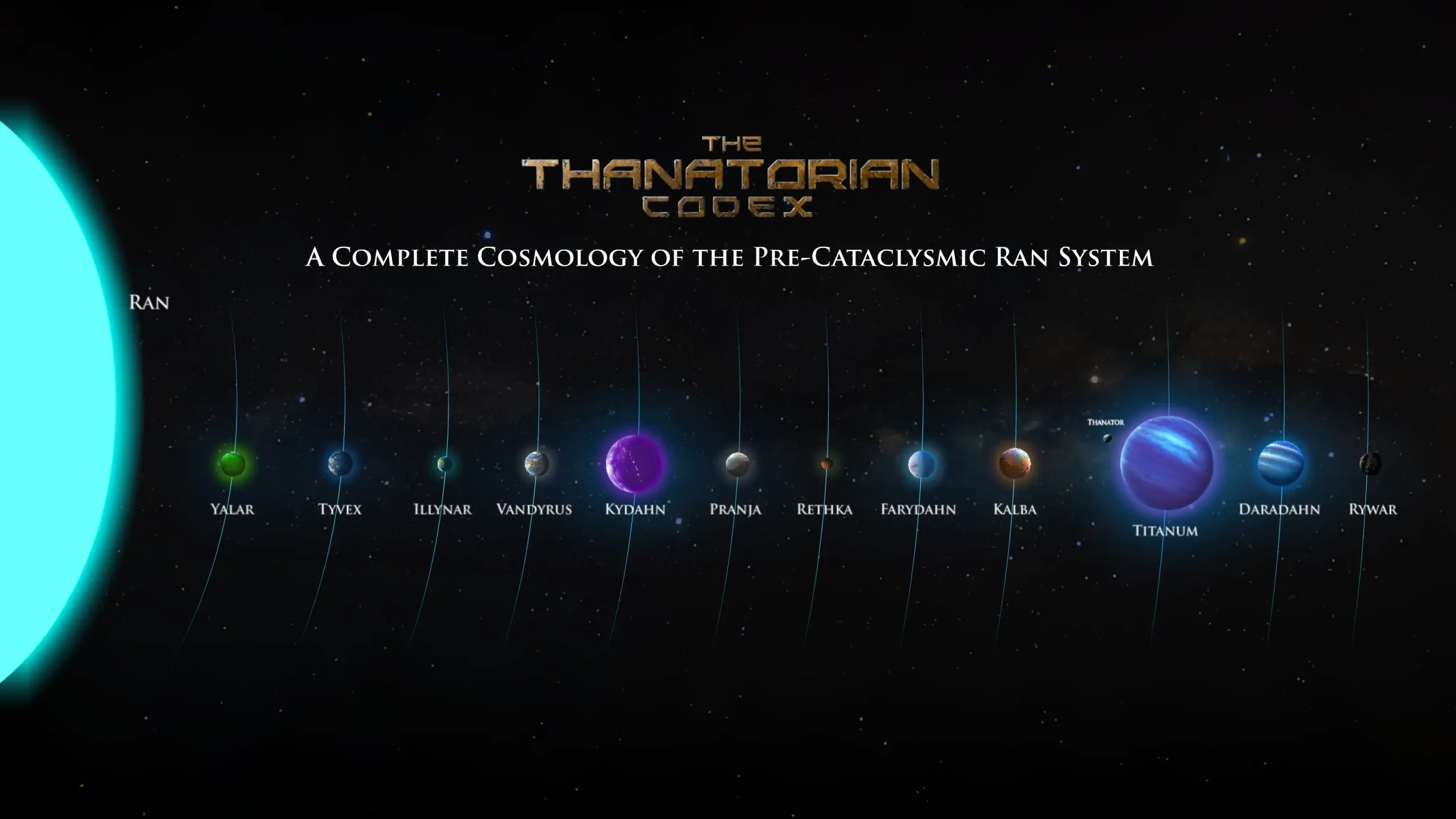

Thanator was one such expression, no more exceptional than any other world that burned bright and fell hard within Ran. Its rise and collapse were not aberrations but expected outcomes within a system that treats planets as instruments rather than homes. The same is true of its sister worlds: each was calibrated to fulfill a role, endure a span, and then either be absorbed, diminished, or discarded as conditions demanded. Survival within the system was never proof of virtue, only of temporary utility.

This is the deeper truth obscured by local histories and heroic chronologies. The Vandyrian Empires are not a lineage that can be traced cleanly from origin to end, but a civilizational machine that renews itself by repetition. It has crossed galaxies, nested itself within layered realities, and endured collapses that would have annihilated lesser structures. It does not remember worlds the way worlds remember themselves. It remembers only patterns that worked, and failures that instructed the next iteration.

Thus, any world of the Ran system—Thanator included—must be read not as a tragedy in isolation, nor as a unique cautionary tale, but as a single verse in a composition written across deep time. To understand one world fully is to recognize how replaceable it always was, and how deliberately it was made so.